Email address: dana@rosswoodwork.com

Web address: danarosssculptor.com (yes, three s’s in a row)

Phone: 404-889-2366

Artist’s Statement:

The foundations of my skill as a wood sculptor are the decades I spent as a carpenter, cabinetmaker, and furniture maker.

I grew up in rural New Hampshire surrounded by a spirit of self-sufficiency and left school with an understanding of art history. I turned to carpentry because I enjoyed working with my hands.

After college, I traveled North America and ended up on Point Roberts, a peninsula of US territory that hangs down from western Canada below the 49th parallel. There, as an informal apprentice to a carpenter, I learned to build houses from the ground up. While in the Pacific Northwest I was also influenced by Northwest Coast Indian art and have often used a semi-angular curve in my designs.

Wanting to explore more of my country, I next went to New York City, where I learned state-of-the-craft techniques in a custom cabinet shop, and enjoyed being surrounded by contemporary furniture styles and art from all over the world.

A search for compatible weather brought me south to Atlanta where for the last 20 years I’ve built many projects, including Buckhead penthouses and music recording studios.

All along the way I’ve kept an interest in wood as a creative medium at the leading edge of design, whether in fine woodwork, cabinetry, or furniture. When I think of woodworking, I think of joinery and other techniques that are suited to wood’s chemical and physical characteristics. The result has been constant experimentation and the taking on of challenging projects with an eye to innovative solutions.

Several years ago, I began creating art pieces more frequently, and these days, creating wood sculptures is my chief activity and my source of endless delight.

Biography:

The Wood Stork

by Suzanne Autumn

Dana McCulloch Ross grew up in the coastal New Hampshire town of Stratham, where his parents owned a 90-cow dairy farm. Almost as soon as they could walk, Ross and his siblings were doing farm chores. “To me, that wasn't work,” Ross says. “I'd be daydreaming while I watched the morning dew sparkle on a field full of yesterday's cut hay. When the hay was dry, I'd happily spend hours on the tractor raking it into rows.”

“Working with our animals—horses and a few goats as well as cats, dogs, and the cows—I discovered that animals like to have fun too. I believe that a farm kid's exposure to the natural world develops an aesthetic appreciation, along with a strong work ethic and the determination to finish any task the kid is given.”

As a teenager, Ross became passionate about photography and was influenced by the works of Edward Steichen. Ross says, “I preferred to work in black and white because when color is absent, composition and detail take precedence, helping us to perceive things in a fresh new way.”

In his twenties, Ross moved from New Hampshire to Point Roberts, Washington, a small US community on a tiny peninsula that juts into Puget Sound just south of Vancouver, British Columbia. Because Point Roberts is located below the 49th parallel, it is United States territory and part of the state of Washington, rather than part of Canada.

On Point Roberts, Ross found work with a carpenter and learned how to build wood houses. In the process, Ross began to study the nature of wood—how boards cut from different tree species bent and flexed, how they accepted diverse finishes, how two or more pieces could best be joined for maximum stability and endurance. “I loved the feel of wood and the smell of a fresh-cut piece of timber. Can't say I've ever tasted wood, but I might have enjoyed that too.”

Ross's art training consisted of college art history and humanities courses and his own reading, along with visits to galleries and museums. Becoming aware of the continuous flow of art through different time periods and civilizations was necessary, his art history professor maintained, in order not to destroy supporting traditions. Ross learned that archetypes such as “the explorer” or “the visionary” thread through all cultures and throughout history, although they alter with time, so that a modern “explorer” might be an astronomer who uses a radio-telescope to wander through the universe.

Ross also made fortuitous discoveries – for example, when he lived in the Pacific Northwest, Ross became intrigued by the wood carvings of the Haida,Tlingit, and Kwakiutl Native people. He can trace their influence in many of his wood sculptures, including his earliest pieces, created while he lived on Point Roberts.

After moving from Point Roberts to spend a few years in larger population centers in Washington and Oregon, Ross eventually headed east. He found employment in Manhattan as a custom woodworker, building high-end cabinetry and furniture. For the next five years, Ross learned new skills from the many talented designers and craftsmen with whom he worked. Ross built everything from spiral staircases to one-of-a-kind furniture pieces.

The wood art that Ross created during his time in New York City was influenced by the general ambiance of the city, and specifically by the year Ross spent living in the famous Chelsea Hotel and interacting with its zany residents, including actors, musicians, and other artists.

Fascinated by the possibilities of wood as a medium, Ross learned many of his woodworking techniques over the decades of his career as a custom woodworker. Ross's motivation in learning any new technique is, he says, “The sheer fun of mastering another aspect of my chosen medium. For example, it's extremely important that I can distinguish between kiln-dried wood, which has become rigid in its cellular structure, and air-dried wood, which maintains its original flexibility and can be bent into new shapes.”

Eventually, Ross decided to strike out on his own, and chose to move to Atlanta, Georgia. In a suburb of that city, Ross purchased a 100-foot-long horse barn that had been built for the U.S. Cavalry during World War I. The barn, with its pre-Halifax, locally formed concrete blocks, 24-foot-high ceilings, wood trusses that spanned its 36-foot-wide roof, and several dozen windows—one for each horse's stall—made a fantastic woodworking studio. There, for more than twenty years, Ross engineered and built pieces to grace some of the most exclusive interiors in the city.

Ross crafted furniture and built-ins for interior designers, sound studio engineers, and individuals who wanted one-of-a-kind pieces. Often this required developing his own techniques to solve architectural and design problems. Ross has incorporated those methods into his sculptures.

A number of woodwork creations from Ross's Atlanta years can be seen on his website, along with his wood sculptures. Because Ross attributes his mastery of the medium to what he learned as a professional woodworker, he believes it is important that his sculpture website include photographs of some of his past work in that trade.

In Atlanta, Ross also pursued a variety of other artistic paths. For a number of years, he designed and constructed stage sets for the former Evoteck Theater in the upscale Atlanta suburb of Buckhead. Ross considers the creation of theater sets to be a form of legerdemain, which he sees as a backbone of art.

A few years ago, desiring to devote himself full-time to wood as an artistic medium, Ross closed his Atlanta business and moved out of the city. Ross's current studio is located on a 3-acre forested tract close to a lake in the Georgia foothills some 50 miles north of Atlanta. There, in the midst of towering white and red oak trees, and of the creatures who call the forest home, Ross continues to create his unique wood sculptures.

Artistic influences:

“In college, an art history professor told me that Picasso was free because he could do anything with a paintbrush,” says Ross, who found his own freedom through solving problems in the woodworking profession, thereby gaining a thorough knowledge of wood's chemical and physical characteristics—information not generally taught in art schools. “Art students aren't usually trained to use wood as an endlessly variable artistic medium,” Ross says, “But I am committed to furthering the use of wood as a unique substance in creative art.”

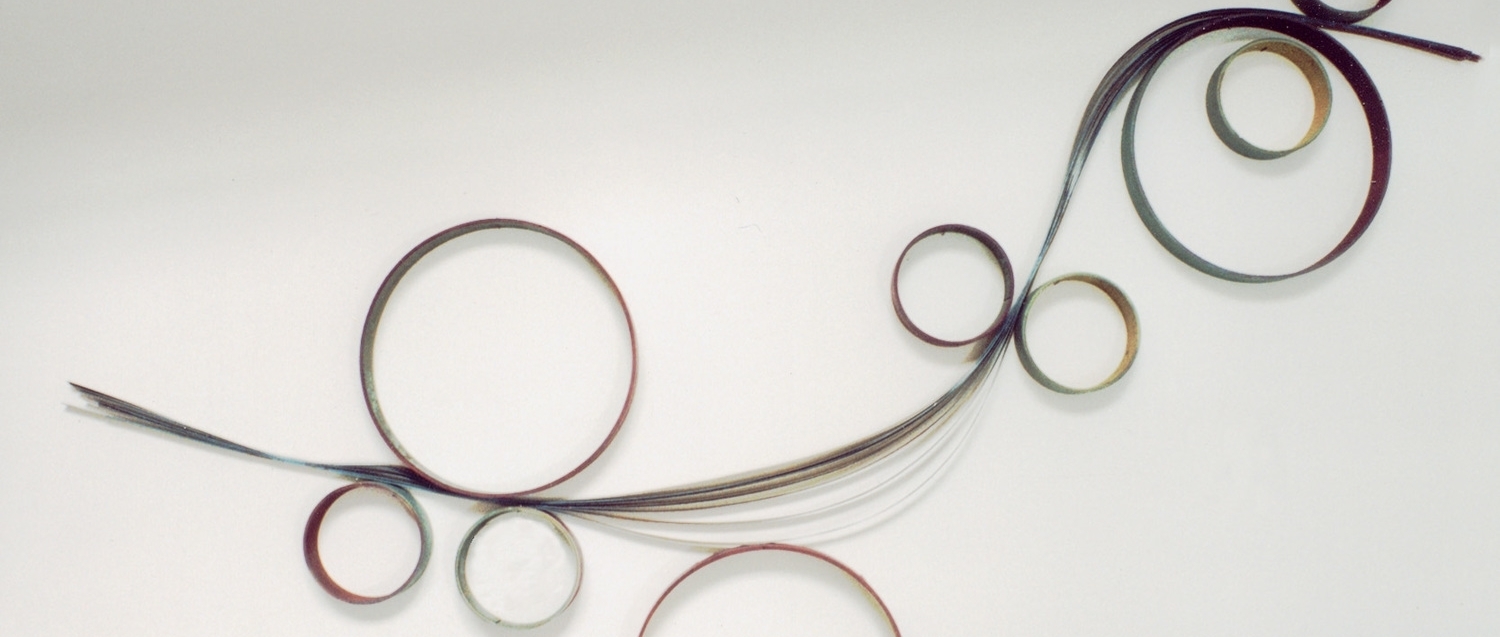

Ross's subject matter expresses an expectation of movement within the piece—an influence derived from the art of the Pacific Northwest. Tribal artists of that area use three characteristics of form: an active or dominant quality, a complementary passive or supporting quality, and a background. “Each of the three could potentially undergo a shift to one of the other qualities, which suggests movement throughout the artwork,” Ross says. “Those artists also incorporate what's called a 'semi-angular curve', which indicates to me that they understand the limitations of geometry when using perfect circles.”

To express originality while acknowledging cultural archetypes remains Ross's primary impetus, which he renders in many of his designs through a sense of movement similar to that in the art of the Pacific Northwest Native artists he admires. Ross is also drawn to the work of Brancusi, because of his flow of forms, and Kandinsky, because of his extreme and innovative abstraction.

The other important influence on Ross's work is his interest in both astrophysics and quantum mechanics—the very, very large and the very, very small. In his wood sculptures, Ross strives to uncover the forms and forces created out of invisible turbulence, which are reflected unseen in our daily lives.